When standing before Abdel Rahman Katanani’s hanging large metallic pieces, Palestine looms large. But in this instance, when amidst the eight works exhibited at the Saleh Barakat Gallery, Palestine does not come forth as the customarily besieged but robust identity, it appears as quizzical remains of an otherwise churning machine of picture making. For Palestine is a machine of seeing, a machine for making pictures. This has been the condition of Palestine for decades, ever since it was forcibly wed to a ravenous Zionist Jewish colonial project. In Jean-Luc Godard’s film Notre Musique (2004), the poet Mahmoud Darwish says it succinctly to a journalist from Tel Aviv played by a youthful Judith Lerner:

Do you know why we the Palestinians are famous? It is because you are our enemies… We are therefore luckless for having Israel as our enemy, for it garners infinite supporters in the world. But we are also lucky for having Israel as our enemy, for the Jews are the world’s center of attention. You have defeated us and given us fame. You have defeated us but awarded us fame.1

This fame is in large part visual. Palestine is primarily a picture-making machine of perpetual suffering, that would have been forgettable, or more precisely inconspicuous, had it not been for the identity of the executioner who paradoxically occupies the attention of the world as the perennial victim. Palestine is forced into a labor of making pictures, mostly of itself for the world to consume but also pictures for itself with which to buttress its identity and document its struggle for justice. The relationship between the pictures-of-itself and pictures-for-itself is certainly unequal and gravely unjust. Palestine is primarily a visual wall of woe over which Palestinians and their allies attach pendants of resilience. Artists and artisans are at the forefront of this effort but what they make, and what they picture is always preceded by the wall of pictures-of-itself, always weighed by the expectation of hanging that one pendant which will hopefully cause the wall to crumble. Being a Palestinian maker of pictures is a hard, almost unenviable, position to be in. The history of Palestine, the struggle, the pain and great expectations are enough to turn any artwork illustrative, identity bound and, to say it bluntly, docilely serving an extra-artistic project.

Abdel Rahman Katanani’s exhibition of eight large metallic embroideries and collaged metallic screens seem to be aware, more so than in his previous work,2 of this thorny problematic. For despite the general and customary identitarian praise bestowed on him as a Palestinian artist, Katanani’s currently exhibited work falters, hesitates, crumbles and is full of hiccups. In short it is at times clumsy and therein lies its relevance. The exhibition’s related showcase of 8 traditional and innovative wall-hung embroideries in the gallery’s smaller space on the ground floor brings this generative clumsiness into focus (Fig.2). Patiently and meticulously stitched by the women artisans of the collective Inaash,3 these stunningly colored and inventively combined embroideries position the work of Katanani in stark contrast. The exhibition’s catalogue informs that the works of the artisans of Inaash, are the prompt and guide for the artist’s work.4 The assumption is that the artist’s work forms an intelligible response that is well inscribed within the historicist narrative of the Palestinian struggle. Both the work of the artisan and that of the artist partake, so the exhibition’s narrative goes, in visually elaborating the manifold facets of a besieged identity. To be fair to the artist, it is necessary to say that the large metallic pieces do try to pay homage to the embroideries, they do attempt to weave, so to speak, complex symbolic compositions. And when, in places where the artist obviously reneges on maintaining the clarity of symmetrical compositions and patterned repetitions, the narrative of the exhibition is quick to justify this formal release, or what I am calling clumsiness, as a facile analogy for the artist’s exasperation at current devastating political and humanitarian conditions in Gaza and the West Bank. But this all goes to show just how difficult it is to be a Palestinian artist and how unlikely it is for one to find a line of flight along which exit the determining structure of pictures-of-itself and pictures-for-itself..

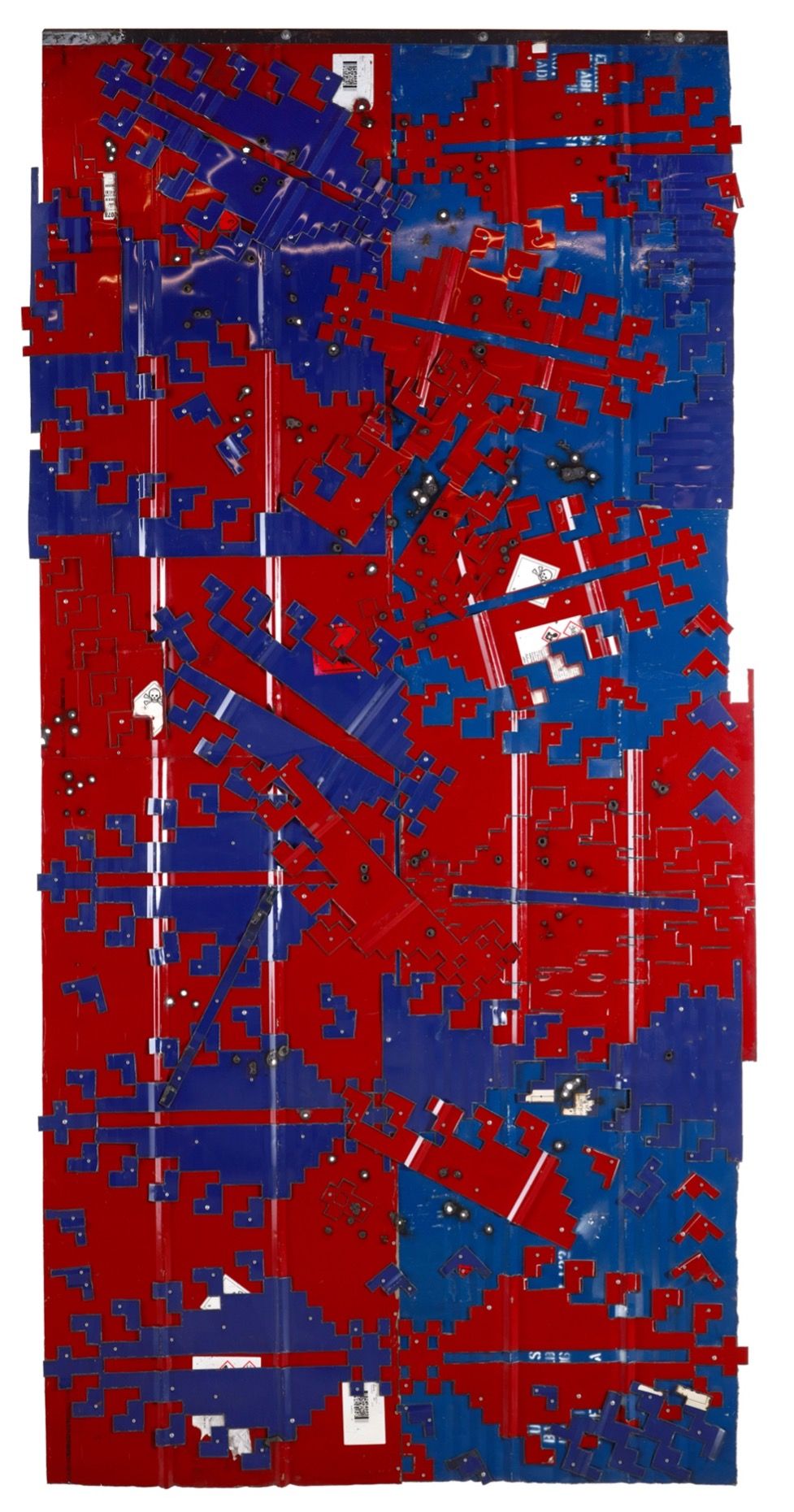

There are passages in Katanani’s work that are neither docilely identitarian nor simply expressionistic. There are patches and clusters of clumsiness, resulting from what seems like an impatience with the formal language of identity. A clumsiness that intimates a disbelief in inherited symbols and patterns, in their professed ability to keep the cohesion of the group and sustain its memory. This may sound perilously close to heresy, especially at a time such as this when cohesion and persistence in the face of the Imperial Israeli war machine are a must. Be that as it may, clumsiness is not necessarily a betrayal. Rather it may be a leeway towards a non-heroic visual language. Katanani’s work seems open to this other possibility even as it stands large and nearly monumental. In the piece titled Forest (Fig. 3), red shapes that approximate motifs borrowed from the repertoire of traditional Palestinian embroidery are strewn about over the varied blue sheets that make up the background. Nothing seems to justify such a release from the studied structures of symmetry except a sort of surrender to casualness, or rather a deliberate turning away from the expectations of what a ‘strong’ work of art is expected to do. A sort of provisionality, to follow critic Raphael Rubinstein’s landmark essay, that is marked by a look that is casual “dashed-off, tentative, unfinished or self-cancelling.”5 In another piece titled Eye of the Camel (Fig. 4), Katanani narrows his palette to the available colors of corrugated metal such as weathered grey, light silver and copper rust. Variegated and mostly truncated shapes occupy the rectangular space without a clear organizational principle. The work is visually entertaining and optically tantalizing but eventually inconsequential, as if unconcerned with its imminent compositional collapse. Moreover, the decision to hang six pieces far enough from the walls to allow the viewer a comfortable passage to experience the back of the metallic pieces decenters the alleged centrality of the frontal image. For the backs when seen and experienced are not simply the secondary and forgettable versos of frontal images. Rather, they haunt the rectos with a gaping emptiness, a gratuitous spray of holes, wayward cuts and fugitive reflections of light.

There is a rogue clumsiness in most of the exhibited works even if the two woven pieces, titled Gaza (Fig. 1) and Palm Tree (Fig. 5) do showcase a diligence that seems to hold on to the narrative of traditional embroidery. Still, it is clumsiness or casualness that make these recent works by Katanani important to behold. They are as noticeably inclined to disinvest from the demands of art and its high values such as artistic authority, creative strength and virtuosity as they are also from the demands of identitarian clarity. More importantly, what these works do is exacerbate and make visible the condition of being a Palestinian artist, always already, preceded by Palestine.

Exhibition Details

Adbul Rahman Katanani - The Story Portals

10 January - 15 February 2025, Saleh Barakat Gallery, Beirut