Retro is one of the more pathologized artistic tendencies. It is often reduced to mere unoriginality and associated with notions of cultural malaise and nostalgia. Mark Fisher, the foremost critic of cultural malaise, wrote in his "The Slow Cancellation of the Future":

I first heard Amy Winehouse’s version of ‘Valerie’ while walking through a shopping mall [...] Up until then, I had believed that ‘Valerie’ was first recorded by indie plodders the Zutons. But, for a moment, the record’s antiqued 1960s soul sound and the vocal (which on a casual listen I didn’t at first recognize as Winehouse) made me temporarily revise this belief [...] it didn’t take me long to realize that the ‘sixties soul sound’ was actually a simulation; this was indeed a cover of the Zutons’ track, done in the souped-up retro style.1

Fisher goes on to mention Retro several times in the piece. He uses the term in discussion of other stylistically anachronistic musical acts such as the Arctic Monkeys and even relates this type of music to “what Fredric Jameson called the ‘nostalgia mode.’” Both Jameson and Fisher are, broadly speaking, critics of the postmodern cultural condition and its capacity for nostalgia.2 They are critical of how it, in contrast with modernity, is plagued by an incapacity to imagine a future world or future aesthetics, whereas modernity, and along with it modern art, was defined by experimentation and utopian ambition. Jameson often associates this postmodern malaise with the artistic form that is pastiche, which brings together styles and motifs from different artistic periods and geographies in a single artwork.3 An example of this can be seen in David Salle’s After Michelangelo, The Flood (2005-6). What these two thinkers provide is a cultural judgment of Retro,4 not an aesthetic one. This is what one might call an “external” description of what Retro is, and a rather negative description at that. Though I would concede that such an external description holds water, that a diagnosis of Retro as caused by nostalgia or as symptomatic of malaise is likely accurate… nostalgia is not synonymous with Retro: only Retro is Retro.

What this article will perform is an “internal” description of Retro. Such an internal description of Retro requires a conceptual understanding of what Retro is in a manner similar to how Fares Chalabi describes the Series as the construction of several variations on a single, problematized idea. This can be seen in Chalabi’s discussion of Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes, which includes a description of the conceptual structure that is definitive of works of Retro as works of Retro.5 From the extraction of such a self-evident and axiomatic structure, a metric of aesthetic judgment will emerge. That is to say, this article will examine the means by which one may judge a work of Retro, as a work of Retro. This is not an engagement with the means of judging a work of Retro as a work of art more generally. Being a great Retro artwork is not the same thing as being a great artwork, anymore than being a great accountant makes you a great human being.6

As is perhaps evident in my concession to Fisher, this is not a critique of his diagnosis of Retro. In fact, this text does not take a diagnostic approach at all, one that links particular cultural pathologies to specific symptoms and thus takes part in forming a causation-based, empirical, posterior form of knowledge in the sense in which David Hume discusses matters-of-fact. Instead, it takes an aprioristic approach to understanding Retro, which seeks to uncover its intuitively salient self-evident nature in the Humean sense of relations-of-ideas.7 Additionally, though the present article has some theoretical comments to make on the work of Fisher and Jameson, it is not primarily engaging with Fisher’s and Jameson’s works as objects of critique. Rather, this article is primarily concerned with Fisher’s observation about Retro and its relationship to indiscernibility. This article will use Fisher’s observation about Valerie as a jumping-off point for its “internal,” axiomatic, conceptual analysis of Retro.

Valerie’s indiscernibility from a song from the 1960s or the 1970s is seen by Fisher as a negative. This is because he sees Valerie as bringing nothing new or original to music. This article will argue that producing a work of Retro that is indiscernible from an artefact, sonic or otherwise, is the highest-level quality a work of Retro can reach, at least insofar as it is a work of Retro. In doing so, this article will define Retro conceptually as a necessarily mimetic art form whose quality should be assessed as such. This will be done largely through a discussion of some of the work of Lebanese photographer Jack Dabaghian.

The Structure of Retro & its Metric

Mimesis traditionally refers to an artwork’s tendency to imitate the world as it is captured by the human eye and/or reality in its rendering of subject matter with extreme precision, in the manner of Jan van Scorel’s Maria Magdalena and the realistic, lifelike precision it is known for.8 Retro also takes part in a mimesis of sorts. Retro mimics artefacts rather than images, in both content and technique. This is an essential characteristic that shields Retro from Fisher’s accusation of simulacrum, the producing of an image of an image.9 An artefact is not an image per se, though it can function as such. An artefact is a remnant of an irretrievable reality. The artefact only acts as an image post factum in its museological context. Therefore, Retro is an imitation of reality and not of an image, and does not therefore take part in simulation.

Retro’s mimesis of an artefact, a real remnant of the past, demands something of Retro. It demands a certain level of historical accuracy from the Retro work, in a manner similar to the demand for accurate costumes in a convincing period drama. The difference is that Retro artworks’ historical accuracy must manifest in the form of an object rather than in a setting, as it does with a period piece. This creates certain limitations on what a work of Retro can be. For example, one could make a very historically accurate period piece, in terms of costumes and setting, about antiquity in the form of a film. But one could not make a Retro film about antiquity since film had not yet been invented in that period. One could, however, make a Retro piece of sculpture from antiquity, as Ali Cherri sometimes does, since different forms of sculpture did exist at the time.10

The more effectively and accurately a work of Retro shapes its mimetic qualities to pass for an actual artefactual object, the better it is as a work of Retro. If one is to compare two works of Retro and attempt to decide which of the two is the better Retro piece (not the better work of art), then one is to compare the extent to which each of these Retro pieces is able to mimic an artefact from a specific time. The height of any Retro artwork is to be mistaken for a genuine artefact. The indiscernibility of a Retro artwork from other artworks from a target time demarcates the ceiling, the limit of quality that a Retro artwork can reach.

Retro is also structurally very different from Jameson’s notion of pastiche, which he associates with postmodernity. Contrasting the two will assist in producing a precise image of Retro’s structure since the two concepts are similar. It is perhaps easy to mistake Retro for pastiche since both make use of earlier work. The difference is that Retro attempts to imitate the reality of a specific period from the past with great concern for accuracy, while pastiche seeks to imitate and combine several past periods in a single work. To understand the difference between the two, consider After Michelangelo, The Flood by David Salle,11 whose work Jameson considered pastiche.12 The painting brings in motifs and styles from different past periods and artworks from all over the world onto the same canvas. Unlike a good Retro work however, Salle’s work could never be mistaken for a piece from any of the periods the painting emulates.

Dabaghian’s Photography

Jack Dabaghian (b. 1961, Beirut) is a Lebanese photographer whose career spans photojournalism, commercial work, and fine art. Some of his artistic projects focus on natural and human rural landscapes in places like Japan13 and Iceland.14 He is especially noted for his use of the collodion process, a nineteenth-century photographic technique that lends his images the visual character of early photography. He has been taking such collodion photographs in Lebanon since the late 2010s.

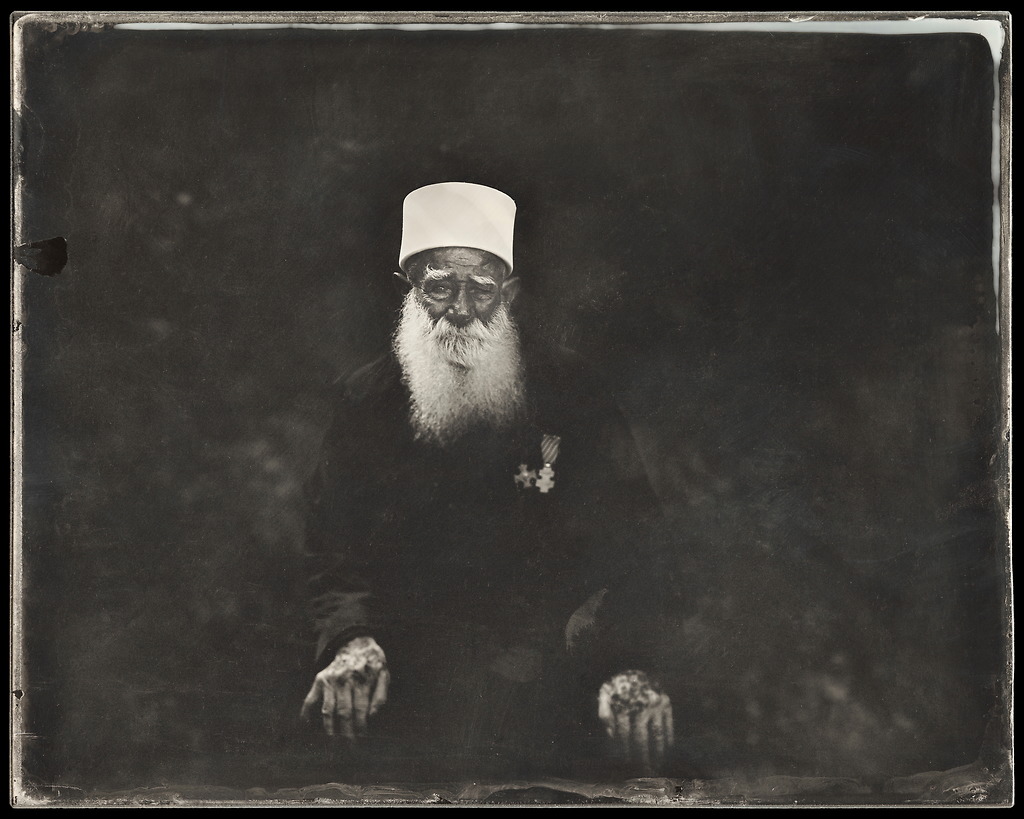

I wager that Dabaghian’s work could be mistaken for an actual piece from the past, an artefact. Dabaghian’s two projects, Masters of Secret and Sentinels, were produced using the collodion process, a distinctly nineteenth-century photographic development technique which involves laboriously coating glass plates in silver.15 The nineteenth-century-ness of these projects is not limited to technique. In Druze, Dabaghian photographs in an anthropological manner that also emerged in the nineteenth century. Dabaghian had in mind the works of nineteenth-century photographer Felix Bonfils, who toured the Middle East photographing much of the region’s ethnic and cultural diversity.16

Right - Fig. 4: Félix Bonfils, Druze Woman Wearing a Tantour, c. 1870. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Druzewomantantur.jpg (accessed 29 May 2025).

In pursuing this project, Dabaghian approached the religious and political leaders of the Druze community, saying, “I want to photograph you the way you weren't photographed in the 1860’s.”17 He wanted to fill in this gap in Bonfils’s oeuvre, though perhaps in a broad sense. The leaders of the Lebanese Druze community vouched for Dabaghian’s photography, which encouraged its clerical class and community members to agree to be photographed. The results were displayed at the Beiteddine Art Festival in 2019 (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 11, 13).

Working closely with Isabelle Rivoal, the head of the anthropology department at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris, to avoid factual mistakes within the Masters of Secret project, Dabaghian concluded that there was no evidence that Bonfils ever photographed the Druze in their villages, but did so in Beirut instead.18 This is likely due to the fact that collodion technology required heavy equipment that was not easy to transport, especially in those days. Dabaghian wanted to do what Bonfils could not: photograph the Druze in their villages. However, regardless of the factuality of Bonfils’ relationship to the Druze, this notion of filling in what was missing from Bonfils’s work is essential to understanding Dabaghian’s Retro. Again, this article takes an aprioristic account which is rather indifferent to the factual, which is only posteriorly salient. It is Dabaghian’s statement, “I want to photograph you the way you weren't photographed in the 1860s” that perfectly embodies what it is to make Retro; to create an image, sonic, retinal, or otherwise, in the technical, formal, and thematic manner in which it would have been produced in another time.

Right - Fig. 7: Jack Dabaghian, The Sheikha, 2018. Sheikha Joumana Ghannam in Beit Eddine Palace, Chouf Mountains. © Jack Dabaghian.

Comparing Dabaghian’s photographs to those of Bonfils, the accuracy of Dabaghian’s Retro appears in both their similarities and differences. Much like Bonfils (Fig. 4), Dabaghian in (Fig. 5) captures a Druze with a rather flat blank background, though Dabaghian’s photograph was shot in a garden, unlike Bonfils’s, which was shot in a studio. Much like Bonfils (Fig. 3), Dabaghian (Fig. 6) captures women amongst stone architectural structures, carrying different containers. In Dabaghian’s case, the woman is seen next to a jug, and in Bonfils’s case, the women are holding baskets.

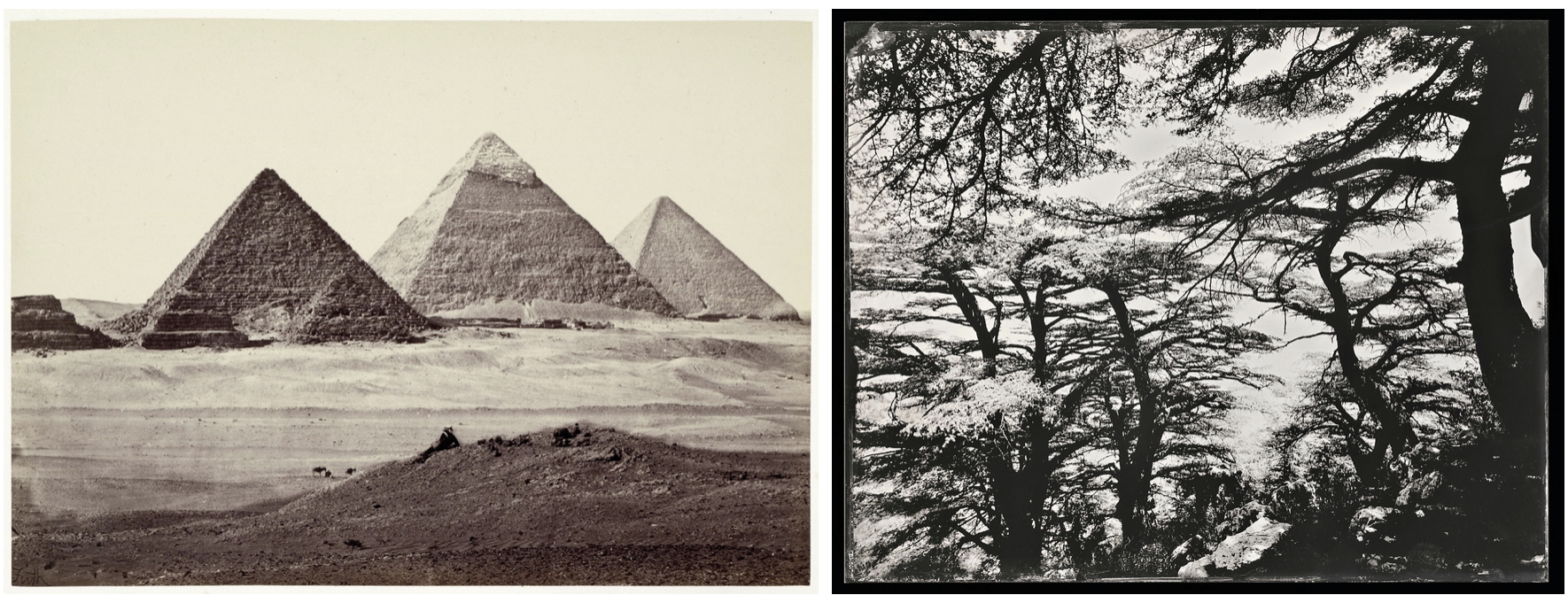

In addition to anthropological photography, another popular mid-nineteenth-century photographic subject was the landscape. It was pursued by many photographers from the period, such as Roger Fenton, Eadweard J. Muybridge, and Francis Frith.19 Firth photographed not only landscapes but landscapes that featured recognizable symbols of different peoples and places.20 Frith was the nineteenth-century photographer Dabaghian had in mind for his next project, Sentinels. Sentinels is a series of photographs of the Lebanese landscape, also taken using the collodion process. They were exhibited in late 2021 at the Saleh Barakat Gallery in Beirut. The photographs often captured images of cedar trees with the Mount Lebanon wilderness in the background. The cedar tree, being the symbol of Lebanon, was captured by Dabaghian, just as the pyramids are the symbol of Egypt captured by Firth.

In Dabaghian’s two projects, we can see the qualities of Retro as discussed above: it attempts to replicate the technique, form, and subject matter of artefacts from a particular time, so much so that they could be mistaken for artefacts from the time they mimic, as with Winehouse’s Valerie.

Right - Fig. 9: Jack Dabaghian, Cedar Canopy, undated. Cedar tree canopy in Maasser el Chouf Biosphere, Lebanon. © Jack Dabaghian.

Assessing Dabaghian’s Retro

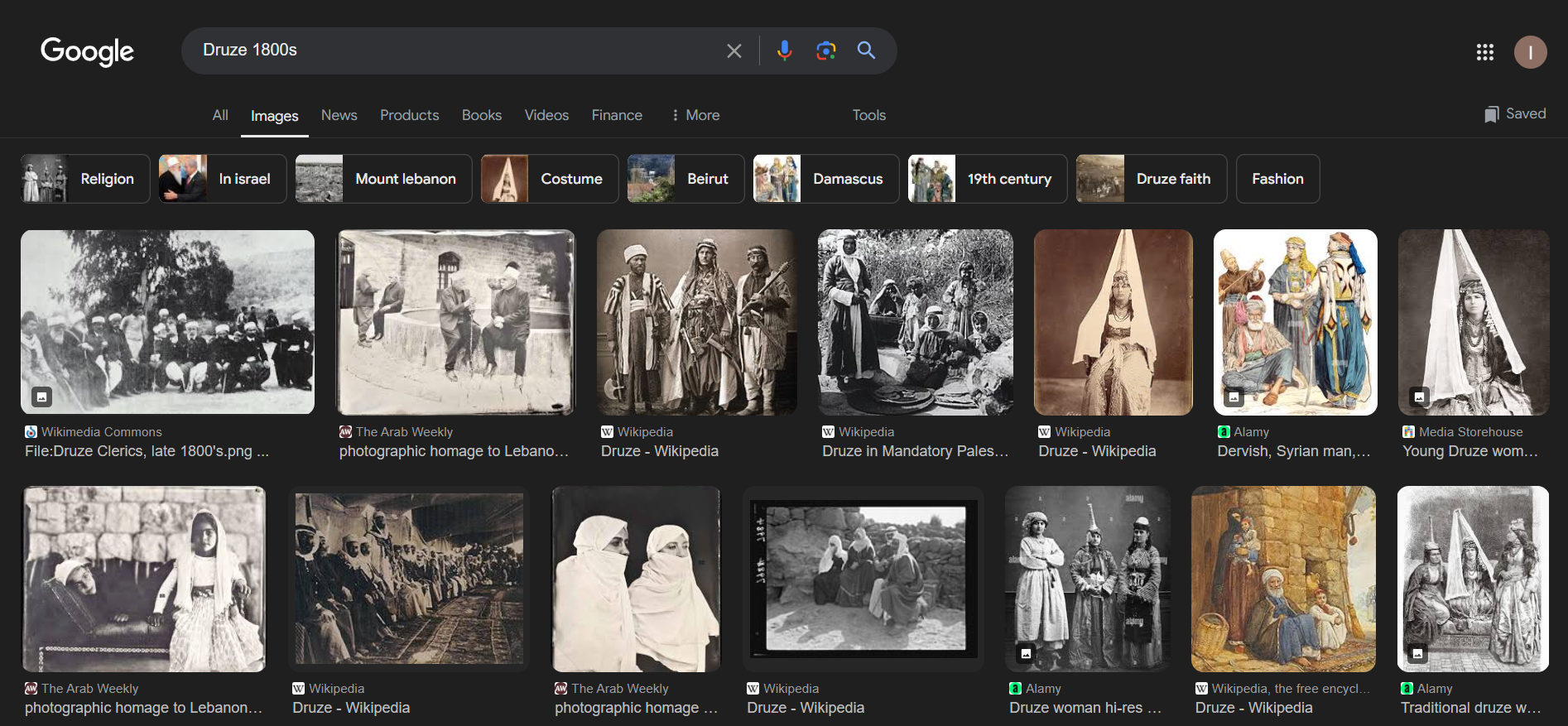

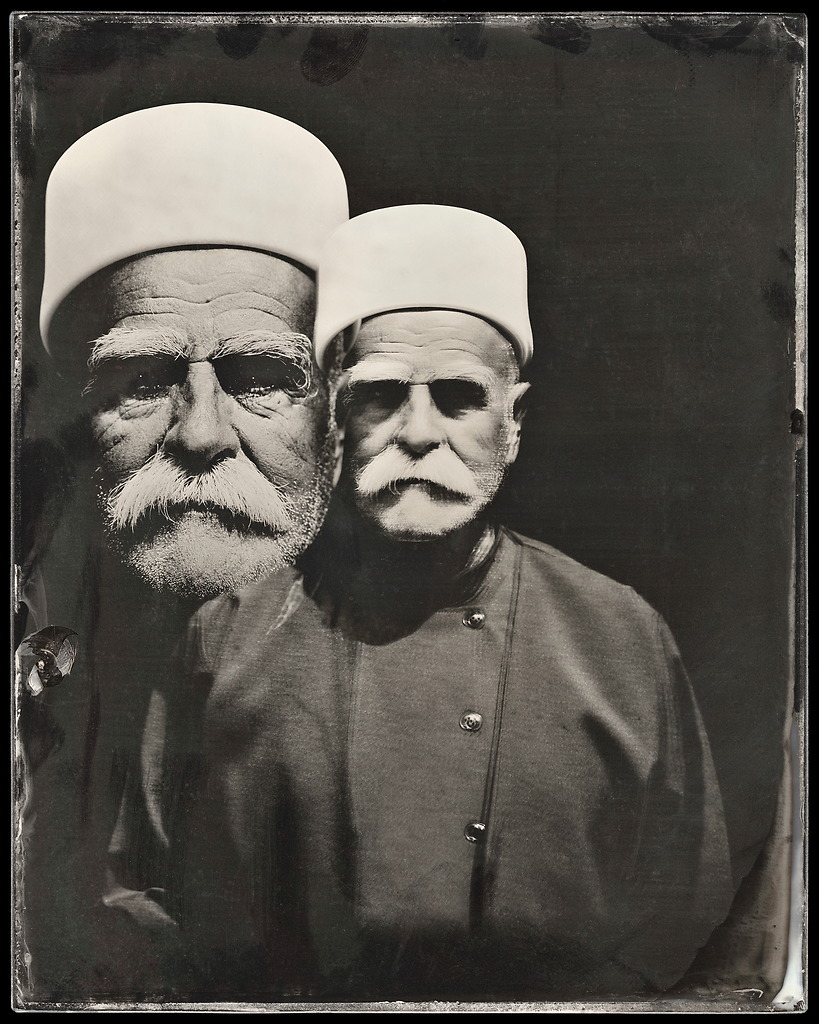

If one Googles “Druze 1800s” or “Druze nineteenth century” or something along those lines, many of the results returned are of Dabaghian’s photographs from the late 2010s. This is revealingly indicative of the quality of Dabaghian’s work as assessed in terms of Retro. This is not to say that Dabaghian’s Retro is perfect. There are certainly some inconsistencies in his works to varying degrees, such as the presence of sneakers on the small boy’s feet (Fig. 13) or the duplication of the Sheikh’s face (Fig. 11). Such a doubling would have been likely viewed as an error in the nineteenth century, rather than a stylized form of emphasis as it appears in Dabaghian’s photograph.

It is not clear that Dabaghian was intentionally pursuing doing Retro as I have defined it, only that Retro as I have defined it is a central form in his work. He seems to be aware of the need for historical accuracy in his work, as is evident in his quote about wanting to photograph the Druze “the way [they] weren't photographed in the 1860s.” However, he doesn’t seem to stick to this definition too strictly.

Certainly, Dabaghian’s Retro is not perfect, but comparing Dabaghian’s Masters of Secret and Sentinels with a work of Retro such as 2011’s The Artist, for example, Dabaghian’s rigor and attention to detail emerge more clearly. The Artist is a film about the transition from silent films to “talkies,” films with synchronized sound. The film is set between the late 1920s and early 1930s, and also, for the most part, has no synchronized sound; it is a silent film until the last few minutes, where we hear dialogue and diegetic sound. The Artist is not a pure Retro artwork since it breaks the convention of silence. However, it is certainly at least partly a work of Retro since it is a silent film about the silent film era. In other words, it imitates both the technique and subject matter of an artefact from the silent film era, a definitive characteristic of Retro. But it is not a very good work of Retro insofar as it is a work of Retro. Firstly, the film was shot using an Arriflex 435, a camera invented in the 1990s.21 Secondly, its themes of a washed-up movie actor from the silent era struggling to find work in the world of talkies is more a thematic concern of the cinema of the 1950s and 1960s with talkies like Sunset Boulevard or Singing in the Rain. In this way, it would be hard to mistake The Artist for an artefact from the era of silent films, both technically and thematically.

Retro, as defined in this article, is a mimetic art form that seeks to recreate the techniques, forms, and subject matter of past artistic periods so convincingly that the resulting work could be mistaken for an artefact of that time. A strong work of Retro achieves a high level of historical accuracy, both technically and thematically. Dabaghian’s Masters of Secret and Sentinels often exemplify this principle through their meticulous use of nineteenth-century photographic methods and aesthetics. While not without minor inconsistencies, Dabaghian’s works demonstrate a commitment to embodied historical accuracy.

Most importantly, Retro should not be reduced to nostalgia or pastiche but understood as a concept with a distinct structure which informs a certain artistic practice—one that, at its best, reconstructs the past with deceptive fidelity. The extent to which it can deceive is the metric by which a Retro artwork is judged as a Retro work and not as an artwork more generally.